Sudbury-White River timetables since 1887, Omer Lavallee's Spanner article from 1953 on the introduction of the Dayliners, and a relief map appear in this post.

Background

Recently the Ontario public broadcaster, TVO, showed a unique 3-hour film about the VIA Rail Budd car consist which provides service to residents along the CPR main line between Sudbury and White River. Generally, these locations are not accessible by any other means. They are a legacy of the CPR's original construction through this remote area of the Canadian Shield.

Today, a few permanent residents, cottage owners, fishing lodges and canoe trippers seem to create most of the demand for this train.

While they still function, here are the YouTube links to the film and its trailer.

Trailer: TRIPPING Train 185

TRIPPING Train 185

Railway Operations During the Steam Era

Originally, the railway was divided into sections for maintenance ... by 'section gangs'. These employees were permanent residents along the line. Taking representative figures from the 1930s: a main line section was from 5.5 to 6.5 miles long, and was maintained by a foreman and three men in summer, and a foreman and two men in winter. Many workload factors were considered when calculating gang size and section length, however, so these numbers are just representative.

Whenever possible, the local maintenance of way employees lived in a village where there was adequate housing available. Failing this, they were hired to live near a particular station having a telegraph office - so an agent or operator could alert the section foreman when there were emergencies to address, such as derailments, washouts, or fallen poles or trees obstructing the right of way.

... Before the availability of small, powerful internal combustion engines, most maintenance of way activities were powered by human muscles. This explains the thin, more uniform population of railway employees and dependents along this line during its early decades.

You will realize that the sectionmen between Sudbury and White River lived in some pretty remote locations. Imagine a settlement where there is silence which is only occasionally disturbed by something as disruptive as a crow. Now imagine the crow is off running errands somewhere. Silence.

The distance from Sudbury to White River is about 300 miles, with Cartier and Chapleau being the main railway towns between these points. These two centres were established as engine and crew change points with the necessary supporting administrative staff, and motive power and car shops. They hosted a relatively large contingent of railway employees during the height of the steam era.

* * *

1968

|

| from: Canadian Rail; July 1969 |

|

| from: Canadian Rail; July 1969 |

After the age of steam was over, here is what the train was like in the late 1960s. With White River embracing its early 1900s national notoriety of being the coldest [railway telegraph station regularly reporting temperatures to newspaper wire services] in Canada ... the Canadian Rail article mentions that the Stevenson Screen containing that thermometer is shown in front of the station in the top photo. One assumes that the operator observed and relayed the meteorological readings.

Below, The Canadian's flag stops are marked with an 'x' while the Budd car trains 417/418 are marked with the traditional 'f'.

|

| from: Canadian Pacific public timetable; 28 April 1968. |

* * *

1990

Having left Schreiber, we were returning east from vacation on a chilly, windy August 18.

After taking the annual photo of the yard from the lawn of the company house at the east end,

this is what we found at 0930hr - the Budd car spotted for its eastbound departure.

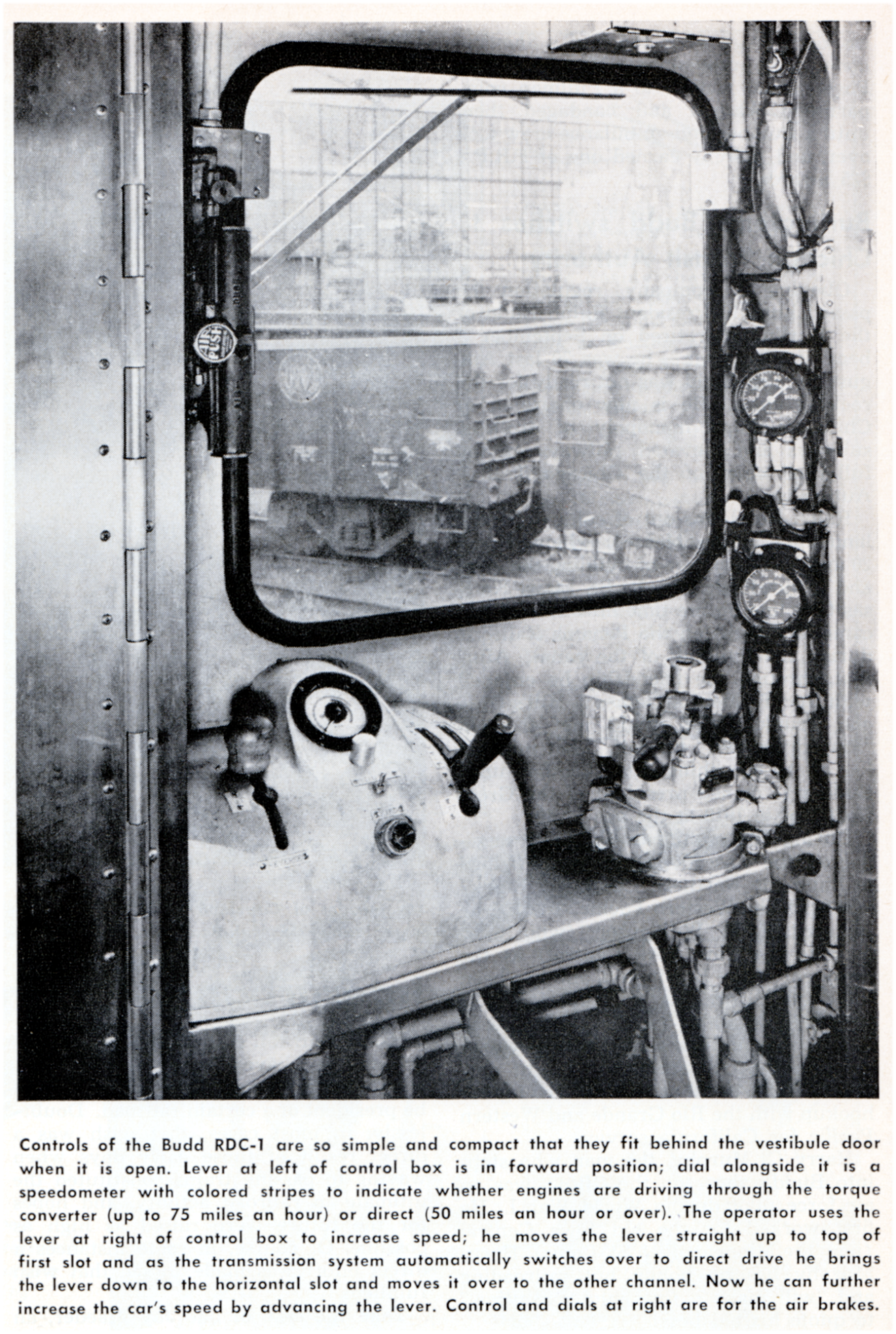

Below: With the trap raised to allow passengers to board, you can see the original layout of the control stand.

This was at the trailing west end of the consist - where you see the step box.

* * *

1981 Map - The CPR Line - White River to Sudbury

|

| from: Atlas of Canada; Dr H W Castner; 1981; Reader's Digest Assn. |

You can see 'our' track running from Sudbury at the lower right corner to White River at the top left.

The Algoma Central Railway runs north from Sault Ste Marie and crosses the CPR at Franz.

1976 census figures

Here is a key to the population markings so you can understand the population density along the line:

Chapleau 1000-4999 residents

White River 400-999

Missanabie 100-399

Michipicoten 50-99 (not on the CPR line)

Franz 1-49

Amyot - population not reported in census

This map shows the local landforms really well.

You can imagine the work involved in the 1880s

to locate and build this line while minimizing grades.

As the landscape is fairly timeless, the map (above)

and natural features (below) are relatively 'current'.

* * *

1901 - Features of the Line

|

| from: Altitudes in the Dominion of Canada; James White FRGS; 1901; Department of the Interior. |

* * *

1887 Official Guide

I have hi-lited the relevant portion of the 1887 transcontinental timetable for the Atlantic and Pacific Expresses.

Back then, it took 13 hours to cover 300 miles.

It probably seemed quite magical to be able to travel across Canada by rail at that point.

|

| from: Canadian Railway Scenes, No 2; Adolf Hungry Wolf; 1985; Good Medicine Books, |

The Priest Plow, with adjustable flangers, leads a passenger train near White River in the late 1880s.

* * *

1916 Official Guide

Again, I have hi-lited the Sudbury to White River section of the line.

|

| Postcard mailed in 1912 showing a westbound at Sudbury. |

The Great War's Battle of the Somme will be starting a couple of weeks after the timetable, above, takes effect. It seems that Trains 1 and 2 are handling the local stops between Sudbury and White River. The running time has been cut down to about 11 hours.

Train 1 runs westbound 1303hr to 0020hr.

Train 2 runs eastbound 0650hr to 1735hr.

* * *

1936 Employee Timetable

I think I bought the next two batches of employee timetables as photocopies,

and I'm glad to have them. However, the print may be a little fuzzy for you.

Sudbury to White River

(Subdivisions: Cartier 34 miles; Nemegos 136 miles; White River 129 miles)

Train 1 runs westbound 1240hr to 2315hr - about 10.5 hours

Train 2 runs eastbound 0735hr to 1715hr - less than 10 hours.

There are no block signals on the line, so the classic system people describe as 'timetable and train order' is being used to regulate traffic movement. While the trains have times listed for each rulebook 'station' (station = location) on the schedule, the time represents when they are due at that station under normal circumstances. For example, this would be important for the purposes of inferior trains which must clear the main track for superior trains - as prescribed by the rules.

... so passenger train times are not necessarily stops at station buildings. Only those times with an 's' beside them are scheduled stops, and times with an 'f' beside them are flag stops.

Where the times are shown in boldface (eg. Train 951 at 5.43) there will be a second identical boldface time for another train somewhere on the same line of the schedule - if you run your finger across you'll find it. Considering all the conditions specified in the rules (there are many) 5.43 is the time of a scheduled meet between two trains (eg. at Kirk siding).

The column with 'D' and 'N' shows the locations of day and night train order operators. So you could infer that maintenance of way section gangs are more likely to be found living at some of these locations.

* * *

1939 Royal Travelogue for the Sudbury to White River Line

Casting about for something which described some of this typical Canadian Shield territory, I remembered this book. Below are a few descriptions from a presentation-style book prepared for members of the press accompanying the Royal Tour of 1939 - King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. The book was also given to key participants at locations visited during the tour. The descriptions are dated and reflect the values and priorities of their era, but they fit 'here' in the chronology we are building of this line. The train has just left Sudbury ...

* * *

1946 - Employee Timetable

Eight months after the dropping of the atomic bombs, the employee timetables, below, reflect the rebound of traffic after the Great Depression during World War II.

The running times of Trains 1 and 2, and the time of day during which they run is virtually unchanged. Between Chapleau and White River, Absolute Permissive Block Signals have been installed (this notation is printed sideways to the left of the station list on the White River Sub sheet). When traffic becomes heavy on a railway line, these signals are designed to keep trains from running into each other - they provide a higher level of safety*.

(* There are only so many timetables and rules and daily exceptions to the timetable ... which humans - eg. engineers and conductors - can hold in their heads while they are 'driving' without forgetting a key detail at the wrong moment. Today, aviation professionals memorize key data, use checklists when key tasks may be forgotten in the heat of an emergency, and electronic alarms add another level of protection.)

The speed and weight of the typical trains operating on a line are used to calculate how long the signal-protected 'blocks' should be. If a train suddenly encounters an approach signal (eg. a yellow light or a semaphore arm at 45 degrees) it should be able to safely stop before it reaches the next signal indicating 'stop'. Beyond the stop signal may be a train stopped on the main track, or a train clearing the main track into a siding for the approaching train to pass. An absolute signal displaying 'stop' must not be passed.

Absolute signals and permissive signals are deliberately different in their appearance. A permissive signal showing 'stop' might allow the train, after stopping, to proceed under particular speed limits and other cautions. And, you never know, maybe the next signal it encounters will allow it to proceed normally!

... For example, maybe the train ahead was stopped and dropping off a sectionman in the bush after he had spent a wild night in Chapleau - causing a stop signal (the permissive type) to protect the train's tailend. But this stopped train quickly got back underway, running at the speed limit again - the following train stopped at the signal, then approached slowly with care, but next signal is miraculously 'clear'.

So absolute signals protect against collisions. Permissive signals do the same thing, but they may sometimes make operations more efficient.

While these coloured signals may brighten up the scenery for the crews and add a layer of safety on busy lines, the underlying traffic control system is still 'timetable and train order'.

If you ever have the time, this classic book interprets all the old rules.

* * *

|

| Unused postcard from the mid-1950s, showing a westbound passenger train arriving at White River. |

1958 - Official Guide

Notice the reference mark that indicates that Trains 417/418 are RDCs.

These Budd car trains run from Sudbury through to Fort William and serve all the listed stations.

This allows Trains 1, 7, 9, 2, 8, 10 to operate on slightly faster schedules.

Because Train 418 arrives at Sudbury at 1300hr, and Train 417 departs Sudbury at 1800hr ...

This suggests that the Budd cars may be based in Sudbury for maintenance, etc.

The Budd car ability to accelerate and decelerate quickly would be valuable

for this type of all stops local train running on this busy bridge traffic route.

Note: The first times for Franz pertain to the daily Algoma Central train ...

From the Sault, good connections could be made with CPR Trains 7 and 8.

To the Sault, your best connections would be via the Budd cars: Trains 417, 418.

Over the years, I have corresponded with two of the operators who once worked at the CPR station, Franz.

You'd at least have interesting people to talk to if you had a 4-6 hour layover there.

* * *

Here is an article by Omer Lavallee on the introduction of the CPR Dayliners

along with his bonus article on the history of CPR self-propelled railcars.