Above: A postcard view, circa 1900, shows a westbound Grand Trunk train passing the Dominion (Bridge) station in east-end Lachine.

About 67 years after the fact, here is a 'modern' employee timetable showing the relative locations of the stations in 1957.

'Lachine' here is the 1888 station which was built to the west of the Lachine Wharf spur switch.

The switch to the Lachine Wharf spur is at Willows.

The location Willows persists here, but the spur segment at the Lachine Wharf has been removed by this time.

The accounts never refer to a 'spur' but I use the term to help with the description of that piece of track.

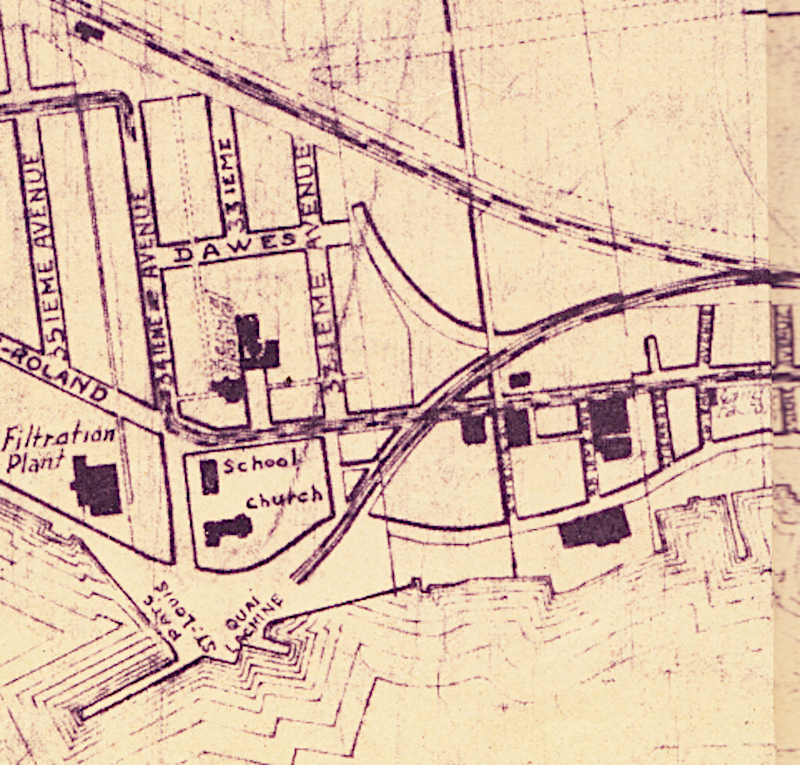

Above, is a municipal map with 1932-1954 features.

The Wharf spur has been truncated.

The wye no longer exists.

The Lachine station (built 1888) is the elongated 'T' at the top left corner of the image.

Willows is the switch where the spur meets the main line.

* * *

A Summary of Events

On 4 December 1890, a five car express train, including one Pullman car, was running 5 1/2 hours late from Bonaventure Station in Montreal with its destination being Toronto. A derailment in the yard at Bonaventure had delayed the train's departure.

Running west for Toronto, the express approached the Lachine Wharf spur in a snowstorm at around 06hr. It departed the main line on the spur switch and the engine and baggage car ran into the St Lawrence River. The engineer Joseph Birse, a Scottish-born engineer with 30 years experience on the Grand Trunk, was pinned in the wreckage of the engine and killed. He was the only person to die in the accident.

A coroner's jury was convened in Montreal to investigate the circumstances of the engineer's death. An internal investigation would have been conducted by the Grand Trunk Railway to determine if any operating rules were violated, and to decide whether any employees required discipline or dismissal. There was no national railway commission at the time, so a federal inquiry into the circumstances of this accident was never conducted.

While all the other clippings come from the Montreal Daily Witness (via Google), the clipping below comes from a Quebec City paper and provides additional details.

|

| from: Quebec Daily Telegraph 4 December 1890. |

* * *

The illustration below documents the accident site, the presence of a wye and the fact that there is double track on the main line.

|

| from: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec |

* * *

On 10 December 1890, the coroner's jury viewed the body of the engineer. The coroner is Jones and the foreman of the jury is S Carsley.

In the Montreal Lovell Directory of 1890-91, there is only one 'S Carsley': Samuel Carsley, living at 507 Guy Street, who is a seller of wholesale dry goods. Carsley & Co. is his wholesale business at 113 St Peter Street next to Molson's Bank - at the place where the Lachine Canal meets the Montreal harbour basin. A large retail operation was also established on Notre Dame. The reason for my curiosity about Carsley will soon be apparent.

|

| from: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec - source publication unknown. |

* * *

Newspaper accounts refer to it as as a 'mixed' jury - having both anglophone and francophone jurors.

The funeral of the engineer was reported on the same day in the newspaper.

|

| from: Montreal Daily Witness, 10 December 1890. via Google |

* * *

The 1885 rulebook of the Grand Trunk (at archive.org) was probably still 'in date' when the accident occurred.

Here is the link to the full rulebook.

Grand Trunk 1885 rulebook

I am including rules which will come up in the questioning of witnesses.

While the switch to the Lachine Wharf only had a left-diverging route, these are the closest applicable illustrations.

* * *

The semaphores (in our case) are two signals protecting the Lachine Wharf spur switch - known as Willows. They are equipped so they can be illuminated at night. They acted as modern 'Approach' signals would. They are mechanically set by the switchman at the Lachine Wharf switch (Willows). In Rule 24, a 'railway crossing' is a track diamond.

* * *

The four whistle sounds (signal for switch) and the one long for a semaphore/station warning will be brought up.

In more modern terms, these would be like a 'call for signals' and a 'whistle at the mileboard'.

* * *

These rules will be raised with respect to conduct of the engineer.

From the Enginemen and Firemen section of the rules:

* * *

Back to the coroner's inquest account.

I am summarizing key points BEFORE each article, because the 'clippings' are hard to read.

My hope is that if you find a particular bit of testimony in my summary interesting ...

you will then go through all the details of the account in the 'original artifact' yourself.

... otherwise my summary has saved you from having to read the rough newspaper text.

- A civil engineer employed by the Grand Trunk named Ford testified.

- Dispatcher G.M. Stone (John Stone was the conductor) was also interviewed by Jury Foreman Carsley.

- Train direction is designated as Up or Down. Up trains are west- and north-bound.

- The Toronto Express (westbound) is Number 6.

- Double track existed on the southern route through Lachine. (The northern route is the original Grand Trunk right-of-way). Except for any 'wrong main running' it seems that left-hand running was in place - making this track its own separate section. It almost seems that the double-track was used to eliminate most dispatcher involvement on this section. Local semaphores were used used by station operators to create safe-following 'blocks' between trains operating in the same direction.

- The Dispatcher GM Stone was responsible for Bonaventure terminal to Lachine Junction (about 2 miles) and St Anne's to Kingston.

- Lachine Junction (map below) is just a couple of miles west of Bonaventure ... where the Grand Trunk route from the Victoria Bridge crosses the route of the original railway connecting the Bonaventure area with the original Lachine Wharf (the Montreal and Lachine Railroad).

- I was curious about Jury Foreman Carsley because he is certain he knows more about dispatching than Dispatcher Stone. Carsley believes that Lachine Wharf spur Switchman Dubois (who is not an operator) is owed a telegraphic message on the status of 6-hour-late No 6.

- Switchman Dubois knows some Morse, and he was diligent about inquiring to Lachine Jct about the status of No 6. However, like others working as operators ... the only information he would receive would be through hearing the OS reporting on the common telegraph circuit. In this case, Lachine Junction OS'ed the passage of No 6 to the dispatcher at Bonaventure. The next OS would be by the operator at Lachine ... to the west of the Lachine Wharf spur switch.

- Switchman Dubois's regular shift was 19-07hr. He occupied the Willows switch shanty which was equipped with a Morse set. He operated the switch to the Lachine Wharf and the remote semaphores (elevated, visible at a distance) which should be used if the main line switch was lined for a Lachine Wharf train ... or if a train was between his semaphores for some reason.

- Jury Foreman Carsley says rhetorically (and later retracts in writing) that it was the Grand Trunk which failed to enforce its own rules. In fact, you will notice a certain laxness in how employees are trained and how compliant they are with the rules (by modern standards).

- Fireman Edwards did not observe the Willows semaphore or the switch target for the Lachine Wharf spur himself.

- They had the scrapers (pilot flangers?) down on the locomotive and visibility was poor from the cab.

- Fireman Edwards heard the warning whistle before they passed* the semaphore, approaching Willows. He assumed that Engineer Birse observed that the switch target showed a white light, indicating it was lined for the main line. (*A special instruction in the timetable requires a stop at the Willows semaphore - where the warning whistle will be sounded. This comes up later in testimony.)

|

| from: Montreal Daily Witness, 11 December 1890. via Google |

On the map below, you can see an inverted triangle of track where the lines from Montreal's Bonaventure terminal meet the track from the Victoria Bridge. Lachine Junction would be in this 'triangle area'. The Montreal & Champlain (i.e. Montreal & Lachine etc) is the double-track GTR route of 1890 which runs through Lachine. The Grand Trunk route shown to the north is the original GTR route. The wye at Lachine (in 1890) is not connected to the main line (see the 'crash illustration', above) as this undated map suggests.

|

| from: BANQ. Map by Montreal Bridge Company circa 1890. |

* * *

- Conductor John Stone testifies, stating the only stop before the crash into the river was Lachine Junction.

- After the sudden stop at the crash site, he ordered flagging protection.

- He attended to the emergency and the rescue of the fireman.

- He says the accident was the fault of the driver for not observing the switch and for not stopping if he could not see it.

* * *

- After the break in the inquest, Conductor Stone seems to change his opinion about who was at fault.

- The switchman should have had his switch set for the main track. He should not have turned the switch until he heard the whistle for the 'junction switch' - a signal which his train would not have given.

- Conductor Stone was busy collecting tickets and did not see the semaphore or switch target himself.

- He thinks the engineer had adequate time to stop the train safely after passing over the switch - before the crash.

- He thinks the engineer must have run against the switch which was lined for the diverging route.

- He says, furthermore, that the switchman should not have allowed the Lachine Train to enter the Lachine Wharf spur after it was occupied by his train - the switch should have been locked for the main line. [You'll remember that Conductor Stone ordered flagging for his crashed Express train's tailend ... and this protected the Express when the Lachine Train was subsequently allowed into the Wharf Spur.]

- Operator Anderson of Lachine Junction (two miles west of Bonaventure) testifies. He reported the passing of the late Express train when it passed Lachine Junction and entered the double track section passing through Lachine.

- Operator Anderson also tells Jury Foreman Carsley et al that his OS of the Express train on the common telegraph circuit is for the benefit of the dispatcher back at Bonaventure. Switchman Dubois would not have a special message sent to him to alert him to the late Express train running before the regular Lachine Wharf train. But anyone listening to their telegraph sounder could have been aware of the fact that the Express train was coming toward Lachine.

- I don't know who the witness Walker is. He states that Dubois at the Lachine Wharf switch is a switchman [at $1/day and not an operator at $1.15/day]. Dubois knows some Morse.

- Walker testifies that Switchman Dubois would be guided by the 'whistle calling for the switch' which would be given at the semaphore before Willows. [Then he would turn his switch for the Lachine Wharf spur. Otherwise his switch should stay lined for the main line. Switchman Dubois testifies in the next piece - watch for his account of his training and how the whistle/switch rules are employed at the Lachine Wharf spur switch.]

NOTE: I don't know that I have pinned down absolutely all of the articles regarding the coroner's jury. To keep these blog posts shorter then 'book length' I am working with what I currently have.

- Switchman Emory Dubois (age 22) testifies. He has been working at Willows for about 5 weeks.

- During his night shift there were 4-5 eastbound freights, but after 21hr, there were no westbounds.

- At the inquest, it was then decided to put down question and answer in French, and then translate them into English. Some of the English jurors are hearing the questions, but not the answers - which Dubois is giving in French.

- In the [8x9 foot] switchman's shanty there is a bench.

- Dubois's [approach] semaphore remained green because everything was all right.

- Although he doesn't know how many whistle sounds came from the Toronto Express, he opened the switch to the Lachine Wharf spur upon hearing the whistle because that was the time for the arrival of the Lachine train.

- The engine which passed into the spur was not that usually seen on the Lachine train. But he concluded that the engine for the Lachine train had been changed.

- The fact that the train did not return to the main line from the wye caused him to wonder if something was wrong.

- The whistling of the actual Lachine train - following the Toronto Express - caused him to conclude that the train on the Lachine Wharf spur was the Toronto Express.

- He had inquired [via telegraph] on the status of the two trains - consistent with the Lachine Junction operator's testimony.

- The engine of the Lachine train does not whistle (four sounds - 'for the switch') when he finds the switch lined for the Lachine Wharf spur.

- Switchman Dubois had trouble seeing the approaching Express train and it took some time for it to reach the switch and enter the spur. [It was the first snowstorm since he began working at that location.]

- Next, after it whistled, he allowed the Lachine train to run onto the Lachine Wharf spur. After about 1/4 hour, he was aware that the Toronto Express was on the spur and that he had allowed the Lachine train to follow it onto the spur.

- Jury Foreman S Carsley writes to the newspaper to clarify his statement about 'the fault lying with the Grand Trunk which didn't enforce its own rules'. He says his statement was just in 'general conversation'.

- The Montreal Daily Witness reporter, via the newspaper, counters this. The witness [I think it would be Bonaventure Dispatcher GM Stone] during/after his testimony would not agree with S Carsley ... that in the dispatcher's stated opinion in his testimony 'it was the Grand Trunk's fault that the accident occurred because the railway had not enforced its own rules'.

- Switchman Dubois's testimony continued that he was 'knocked off his head' [perhaps another expression in French to that effect] when he subsequently heard the 'real' Lachine train whistle for the junction switch. Being 'knocked off his head' he consequently allowed the Lachine train onto the spur behind the crashed Toronto Express.

- With two semaphores (one on either side of the Willows switch) it seems Dubois was asked if the semaphore beyond the switch could have been used to stop a train in this emergency. If I understand the question properly, Dubois said that the semaphore to the west of Willows was not lit by night and he had never had any instruction to light it. This semaphore was for the governance of eastbound trains.

- There was no telegraph communication between Lachine Wharf station and Willows. [Perhaps a message to Dubois could have prevented the Lachine train routing into the Wharf spur?]

- He arrived late at work at 2130hr instead of 19hr because he was trading hours with a co-worker.

- Switchman Dubois did not hear the OS regarding No 6, the Toronto Express, as it passed Lachine Junction.

- He might have been asleep between 01hr and when the OS reports were made from Lachine Junction about the westbound Toronto and Lachine trains.

- The [actual] Lachine train did not stop at Willows and he had no communication with its crew.

- Switchman Dubois testifies to the difference of whistle signals given at the semaphore by through trains and those wanting the junction switch. Given the storm, he thinks he was unable to hear the complete whistle signal of the 'Lachine train' and so he lined the Express into the spur.

- After the switch was lined into the spur - admitting the Express - he did not re-line it for the main line. He anticipated that the next train over his switch would be the same 'Lachine train' (in reality, it was the crashed Express) as it came off the wye and spur ... and as it returned eastbound toward Montreal.

- Switchman Dubois testified that relying on the size of the train to identify the Express would not necessarily work as the Lachine train often had seven cars.

- When he started at Willows he asked the operator there [which operator - at the Lachine station?] about his duties and was told that the [Lachine operator OS'd the passing trains - I speculate].

- He had not been asleep at the time when the Express had whistled at the semaphore.

- Switchman Dubois had worked for the Grand Trunk for 3 years as a switchman.

- He was never examined by anybody regarding his duties at Willows.

- He understood that the normal position of the switch is lined for the main line.

The conclusion of the inquest account will become somewhat exciting.

* * *

Bonus Features

Four years before the accident, here is the frequency of train traffic between Bonaventure and Lachine.

|

| Grand Trunk 1886 public timetable from archive.org |

Here is the link to the timetable at archive.org.

* * *

On the main line: Lachine station (built 1888) looking west circa 1914.

The reflectorized oil platform lamps are typical.

Notice the semaphore at the right.

|

| from: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec |

* * *

Here is the Lachine Wharf station (undated) - looking back toward the main line.

It has different platform lamps. You can see the point where power or telegraph lines enter the building.

|

| from: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec |

* * *

The beautiful map of Lachine below is from 1856.

It is part of a larger sheet/plan subdividing a tract of land into building lots.

|

| from: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec |

At the left, is the track (later a spur), wharf and station which is referred to as Lachine Wharf in our 1890 case.

Of course, this is before the Grand Trunk's continuation of this route toward Dorval.

And its subsequent double-tracking.

To the right is the original wharf used by the 'Montreal and Lachine Railroad' and its other corporate successors.

You can see that this wharf was designed to load rolling stock on a 'car ferry' bound for Caughnawaga (Kahnawake) and the US via Hemmingford, etc.

After the Victoria Bridge was completed, this process was unnecessary.

Speaking personally, three generations of our family attended the 'Scotch Church' shown here.

To us, it was known as St Andrew's United.