This post is the second which looks at the ideas presented in the following paper:

Interwar Rail Construction in Saskatchewan and Alberta: An Evaluation

by Charles W. Bohi, Leslie S. Kozma

Presented at the Annual Meeting of the

Prairie Division, Canadian Association of Geographers in 2007

(Mr Bohi noted my interest in the area and emailed a copy.)

(Mr Bohi noted my interest in the area and emailed a copy.)

* * *

The link to my first post is below:

I actually found a link so you can download the research paper itself in PDF form:

The images I insert are not from the paper.

Square, indented paragraphs contain only my ideas or comments.

My brief account will only skim over some key elements of the paper.

My brief account will only skim over some key elements of the paper.

* * *

Previously, the authors examined information related to the 1932 Duff Commission:

1. Why the Interwar branch lines were built.

2. Whether the CNR was the aggressor.

* * *

This post looks at the third and final question from the paper:

3. Was building these [Prairie branch] lines a 'Disastrous Mistake'?

Generally, the Interwar branch lines were constructed to serve Prairie farmers.

They were growing wheat - an important Canadian export.

They were growing wheat - an important Canadian export.

As noted previously, a few of the branch lines were built for the purpose of providing transportation services to coal mines in the southern Prairies. As coal was a convenient fuel for space heating in the Prairies during this era, some of the branch lines shortened the distance it had to be moved - saving money for Prairie coal customers, including the wheat farmers.

Continuing with the theme of serving wheat farmers:

These Interwar branch lines included 605 locations

where the railways built sidings and other facilities to receive freight.

where the railways built sidings and other facilities to receive freight.

By 1936, 57 of these locations were incorporated as villages (50 people),

with 2 communities incorporated as towns (500 people).

with 2 communities incorporated as towns (500 people).

In addition, 143 locations had permanent depots

(i.e. station buildings - with 'agents' to conduct local railway business).

(i.e. station buildings - with 'agents' to conduct local railway business).

The fact that almost one quarter of all locations saw station buildings erected

suggests that a significant amount of local commercial activity took place on these lines.

* * *

suggests that a significant amount of local commercial activity took place on these lines.

* * *

A stretch of track we drove along ... as part of a vacation, and shown in another post ... the Fife Lake Subdivision, between Assiniboia and Big Beaver ... is examined in The Weyburn Region - see the References section of the 'Interwar Rail' PDF above. I could not find this Weyburn section in a readable form on the internet. Here are some of the authors' ideas on the Fife Lake Sub ...

|

| from: CPR employee timetable; April 1950. |

|

| Atlas of Canada; 1981; Reader's Digest. |

Considering the Fife Lake Sub example:

The Interwar branch lines were built to serve Prairie farmers. However, life for the farmers and their families had to consist of more than simply growing and transporting wheat. Using the Fife Lake Subdivision as an example ... the line brought in the essentials of life for those living in this area of Saskatchewan. This line also fostered social institutions and activities - and a sense of community - which softened the often harsh realities people faced in this area of the Prairies.

In 1960, 68 cars of coal were delivered to the 8 stations on the Fife Lake Sub which had coal dealerships.

In 1969: 10 locations had post offices; 6 had general stores; 7 had gas stations; and Rockglen, the largest settlement, had a grocery store. Farmers could obtain bulk oil deliveries at 7 of the locations (farms often maintained their own bulk tanks with hand pumps for refueling tractors, combines, etc). Rockglen and Coronach also had lumber yards.

The communities on the Fife Lake Sub were also social centres - 6 had elementary schools, and Rockglen and Coronach had high schools. Churches were located at 5 settlements, and 5 settlements had a total of 8 ice rinks.

The following passage is taken from the research paper

and it portrays a time when the train was central to this community ...

and it portrays a time when the train was central to this community ...

If the railway branch lines had not come closer to the farmers, the farmers would have had to transport their grain by road using their own horse-drawn wagons ... or early rudimentary trucks - for the few who could afford them. Depending on the state of the grain market, this could have had a major impact on farmers' incomes.

As noted previously, the rural (often unimproved, dirt) roads were poorly maintained in the 1920s and 1930s and winter snow clearing was not provided until after the Second World War. (One source I read suggested that the Dominion Land Survey and its system of road allowances left farmers with an inefficient grid of too many roads which exceeded the local government's ability to maintain them.)

In the 1920s, the cost for a farmer moving a bushel of wheat 10 miles to an elevator was about 8 cents.

Today it may seem that farmers were being pampered with expensive branch lines if they only had to travel 10 miles into town.

Keep in mind that 10 miles is the 'ideal maximum' distance which is often cited in historical accounts ... See the maps above. Horses at a walk, pulling a loaded wagon, travel at about 4 miles per hour. A 20 mile round trip would ideally take about 5 hours of travel time.

... This would not include harnessing/unharnessing, resting or feeding the horses ... or waiting in line at the elevator ... or any delays or detours due to road conditions ... or time lost climbing steep grades at a slower rate which called for a brief rest of the horses at the summit.

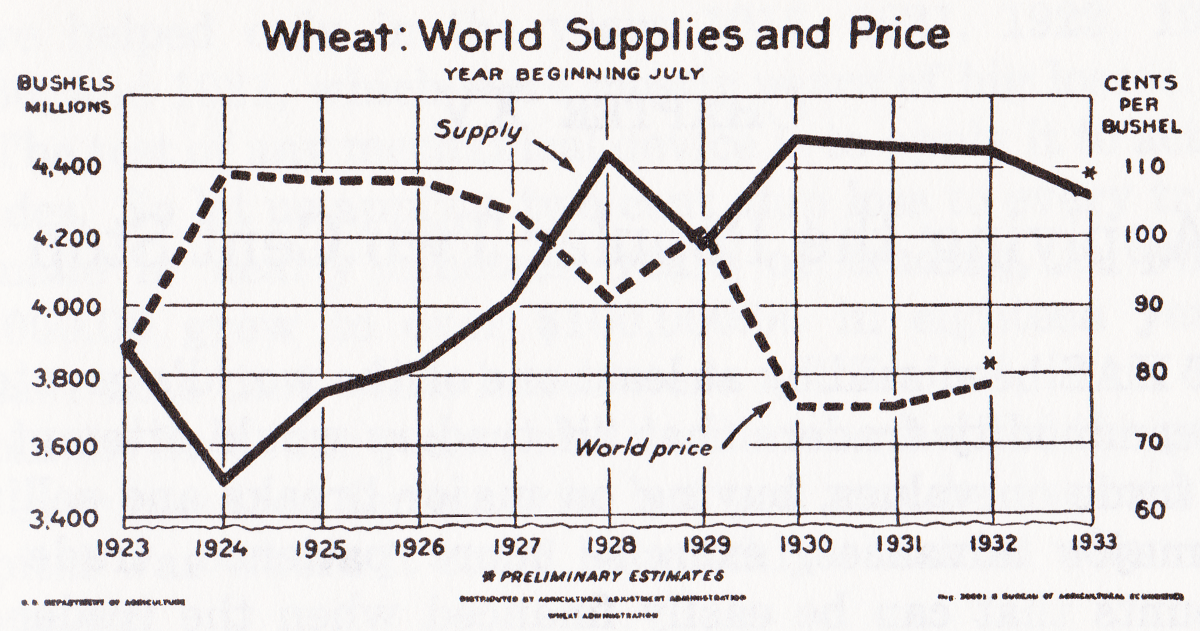

In 1923 (a year of low prices), 8 cents per bushel for transportation to a local elevator was significant because the market was offering about 65 cents per bushel. Consider all the costs faced by the farmer to produce the wheat, and any debt and debt costs, plus clearing enough money from the crop to feed a family for the year, etc.

In the Interwar years, the Canadian government made the decision to assist farmers, and their efforts to produce wheat for export, in a reasonably economical way. The government supported the building of more railway branch lines through areas where farmers faced long road hauls to get their grain to market.

Eleven CNR branch lines (cited in a Senate debate in 1924) cost $9.5 million ... for 397 miles of line. They would carry about 10 million bushels of wheat and 2755 cars of other freight per year. It was calculated that they would save farmers on the lines $1.3 million per year.

Before changes to federal regulations which allowed the railways to abandon branch lines holus bolus in the 1990s (I believe) only a certain percentage of each system could be abandoned in a given year. Regularly, there was the solemn-faced submission by CNR and CPR officials of the following figures to the regulators ... for the branch lines they wished to abandon that year.

GROSS REVENUE minus EXPENSES equals NET LOSS ... for the branch line.

... In conjunction with evidence presented to the Duff Commission (for 1923-1930) the CNR showed significant net losses for 10 specific lines.

... However, the authors point out that the 'branch line freight cars' usually travel over the system OUTSIDE of the isolated branch line ... out where a railway's cost per ton-mile is lower. When one considers the whole freight movement ... which includes the more efficient sections of line (longer trains, heavier traffic per mile of track ... transportation 'in bulk') ... the net loss associated with the traffic originating or terminating on the branch lines is considerably less.

... So, instead of being a 'disaster', the cost of the lines was more reasonable ... if the point was to encourage farmers to contribute to the nation's economy by growing wheat which was mainly for export. And that's what the government had been trying to do.

* * *

The Interwar Lines in 1935

When the last lines of this planned network were eventually completed ... in the middle of the Depression ... ecological problems (droughts, grasshoppers, topsoil loss), crop failures, and the Great Depression, itself, killed any enthusiasm for building more branch lines on the Prairies.

The authors provide these points for readers to consider:

- The lines constituted 30% of the rail network in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

- The country elevator system reached its peak in the 1930s - about 29% of total grain delivery points were on the Interwar lines.

- In Saskatchewan and Alberta, 27% of all competitive points (where two or more elevator companies had country elevators) were on Interwar lines.

- From the 1931 census it was found that about 73% of all farms were within 10 miles of a railway station ... only 2% were more than 25 miles away.

In spite of the criticism levelled at the Interwar lines in the Duff Commission report, the authors point out that no wholesale abandonment of the lines was prescribed by Duff - i.e. to avoid throwing good money after 'bad'. In fact, these lines were subsequently key in the transportation of western grain for decades.

Abandonments for some of these lines were as follows:

1950s ... 115 miles

1960-1963 ... 370 miles

1963-1975 ... 525 miles

... As Prairie branch lines were being abandoned in the 1980s and 1990s, I remember a lot of local concern expressed that the infrastructure cost of transporting grain was being shifted from the abandoned lines to the municipal/provincial public highway system ... as farmers preferred larger and larger trucks (not horse-drawn wagons) as the most economical short-haul method to the nearest surviving railside elevator.

Addressing some of the conclusions of later historians, the authors note that much of the rhetoric surrounding these lines during the 1930s originated from the general climate of bitter political animosity between the Conservatives and Liberals. The conventional wisdom was that the Prairie branch line system was overbuilt because of the actions of the CNR. In particular, Sir Henry Thornton (by then deceased) had been a cheap and easy target for the Conservatives.

Yet, in the face of this conventional wisdom, the Interwar lines continued to be useful ...

Yet, in the face of this conventional wisdom, the Interwar lines continued to be useful ...

In 1963, using the 10-year average of 465 million bushels: about 25% of grain was still originating on the Interwar lines.

The authors close with a nice (almost poetic) descriptive passage from a Queen's University economist in 1934 ... and I encourage you to download the PDF to have a look at it.

* * *

End of my summary of

Interwar Rail Construction in Saskatchewan and Alberta: An Evaluation

by Charles W. Bohi, Leslie S. Kozma

PDF here:

* * *

Inspired by that last quotation, today, I purchased a copy of the 2015 biography of economist W.A. Mackintosh (1895-1970). Here is a passage from 1935 in which he describes the realities of farmers in the Canadian 'Wheat Economy' on the Prairies.

"The wheat farmer in western Canada is engaged in a business subject to unusually sharp fluctuations, imposed on it in greater or less degree by pronounced variations in rainfall and the other climatic conditions of wheat growing, and by the necessity of competing in a far distant world market for the sale of a raw material. In these facts of a commercial agriculture in which a high degree of variability is inherent will be found the centre of the economic problems of Western Canada."