You need to have and to maintain a plan to stop your train before you start to pull. This is wise advice pertaining to the skilled use of air brakes to control a heavy train rolling along on its nearly frictionless guideway.

I singled out a thin booklet for a light blog post about a technology which will soon be forgotten.

Finding more and more references, the project turned out to be broader and deeper than originally expected. This was not the brief 'vacation' from the Pool Train trilogy which I had been seeking!

Some recent photos from the 1980s reminded me of the passenger car, to locomotive cab, communicating system which was once very common. Even when portable two-way radios became widely available in the 1960s and 1970s, its use was mandated for important communications while radio was a backup system ... as you'll see.

In a few cases I observed in the 1980s, if a 'modern' conductor gave a proceed message via radio, some engineers would not release the brakes and advance the throttle until this old system was used for the highball.

Just as younger people today and in the future will be surprised to learn of this primitive system used before radio ... I was surprised to learn about the downright dangerous system in use before the development of air brakes.

* * *

The pyramid of common carrier safety is built out of gravestones.

The following well-known Canadian accident supplied ten slabs to the safety edifice.

|

| from: Railways of Canada; 1972; Nick & Helma Mika; McGraw-Hill Ryerson. |

As trains became longer, and as locomotive crew duties and distractions multiplied, it became more difficult for the train crew to attract the attention of the engine crew, so a signaling system was developed ...

On passenger trains this involved a bell mounted in the locomotive cab. To enable the train crew to signal using the bell ... or to obtain the engine crew's attention ... a rope was run along the outside of the train for its full length. Pulling on the rope was supposed to ring the signal bell or 'gong' in the cab.

On February 28, 1874, a Great Western Railway train was operating between London and Komoka, Ontario. As I recall (without re-reading) the details of the extensive testimony at the Coroner's Inquest from the newspapers of those days ...

Because of the train consist: baggage cars, petroleum tank cars and a single coach ... it was decided that the bell rope would not be strung. The past experience of the crew was that tank cars in the consist would catch on the rope on curves, causing the locomotive signal bell to ring excessively ... communicating false 'signals'.

When the train was underway and travelling at over 30 mph, a poorly secured oil lamp upset, setting fire to the wooden coach. Fanned by the wind and train speed, the fire quickly threatened all the passengers on board.

As it was winter, it would not be surprising that this coach at the end of the train was obscured by steam and blowing snow. There was no bell cord and lantern signals were probably not visible as the engine crew focused on the road ahead. In this period before air brakes, the conductor was unable to dump the air to stop the train and to enable the passengers to exit the burning wooden coach.

Eventually, the conductor, climbing over the cars, reached the engine and communicated the emergency. Beyond the ten passengers who died, you can imagine there were other passengers with serious burns for which there was little medical treatment or rehabilitation available.

Five years after this tragedy, here are the applicable communicating signal rules from the railway's rulebook.

|

| from: Archive.org |

... Rule 99 is not much of a procedure from our perspective today.

In the Standard Code (of operating rules) of the Association of American Railroads, the first reference to Bell Cord Signals was in 1887.

"Air Whistle or Bell-Cord Signals" were first standardized and published in the Standard Code in 1899.

The following diagram from 1908 shows the New York Air Brake communicating signal system.

'The entire study of air brakes is just high pressure air moving to areas of lower pressure.'

The car discharge valve had a length of cable inserted through its eye.

The other end of the cable was secured near the ceiling of the car vestibule.

This served as the actuating cord.

PLEASE NOTE:

I have NOT included the descriptions or schematics of the valves and other bits

which step down the brake line pressure to the lower signal line pressure.

So parts and pages are missing here.

The Westinghouse plant in Wilmerding, Pennsylvania is shown below in 1897.

* * *

While the 1962 rules were often patched and updated by railways' special instructions,

until they were replaced in 1990 by the CROR,

you'll notice that it was 1) signal line ... 2) hand signals or 3) radio.

* * *

* * *

In a Canadian Locomotive Company cab unit you can see the positions of three whistles:

48 Safety Control Whistle

50 Cab Signal Whistle

51 Overspeed Whistle

The following diagram from 1908 shows the New York Air Brake communicating signal system.

|

| from: The Science of Railways; Marshall M Kirkman; 1908; The World Railway Publishing Company. |

The Westinghouse booklet from 1948 - which you will see shortly - will provide details on how the system operated.

Below, I found a troubleshooting guide for correcting system problems. This handbook for locomotive engineers may have been self-published ... and you'll notice it is dated from exactly a century ago - near the end of the Great War. Perhaps due to wartime material shortages or simply due to the small size of the publishing enterprise, the book itself is cheaply printed on thin paper.

My battered copy has made many trips over the road in someone's overalls pocket or in their 'grip'.

At any rate, this communication technology was the best and most robust system available for almost a century. It seems appropriate to place these references together here - in case someone now or in the future is inspired to research and to elaborate on the technical evolution of this system's components.

|

| Air Brake Manual - A Hand Book for Engineers; Fred L Jones; 1917; James Hope and Sons, Ottawa. |

* * *

Finally, here is the booklet which was going to be presented alone, with a just few train photographs.

Having seen this system used many times, it was interesting to imagine how it might be designed.

The conductor's signal valve in the coach vestibule seems to blow air as it sends the signal.

The cab whistle must blow air to make the sound.

How do you design a single air line signal system to blow air at both ends simultaneously?

... A basketball referee sends air through a whistle, but the inspiration and expiration are two separate cycles - they are not simultaneous.

'Witchcraft to the ignorant, … simple science to the learned.'

Any new technology resembles magic.

Any new technology resembles magic.

'The entire study of air brakes is just high pressure air moving to areas of lower pressure.'

The car discharge valve had a length of cable inserted through its eye.

The other end of the cable was secured near the ceiling of the car vestibule.

This served as the actuating cord.

HSC was a high-speed brake system introduced in 1932 and revised in 1935 for use on Art Deco era light, streamlined trains. It was an electro-pneumatic design which provided quicker and more precise control. The fact that these trains were semi-permanently connected probably made the electrical train circuits less prone to damage from regular coupling/uncoupling.

As the text indicates, the car discharge valves are provided within the locomotives so an attendant working on a problem in the engine room could signal the headend.

Probably, the semi-permanently coupled early 'cab units' used during and after World War Two could also have been recipients of this configuration - e.g. EMD FT units.

OK! .. So do you see the Type 'C' Signal Valve in the diagram above? That is where most of the technological sorcery takes place. The next three images below show its operation.

The first diagram is more schematic and conceptual.

The second diagram is strictly cross-sectional.

The third is a photograph of a Signal Valve with a whistle directly connected to it.

If you are serious about mastering this extinct technology, your best bet is to save and print these three images out because the description ping-pongs back and forth between the schematic and the cross-section diagrams.

As usual with air brake elements ... there are valves normally seated by springs, there are diaphragms which bend one way or the other as pressure changes, and key airflows can be augmented from a higher volume source to create the desired effect.

As they state above, one of their key outcomes is to have the cab whistles sound the same, whether the train's signal line is long or short.

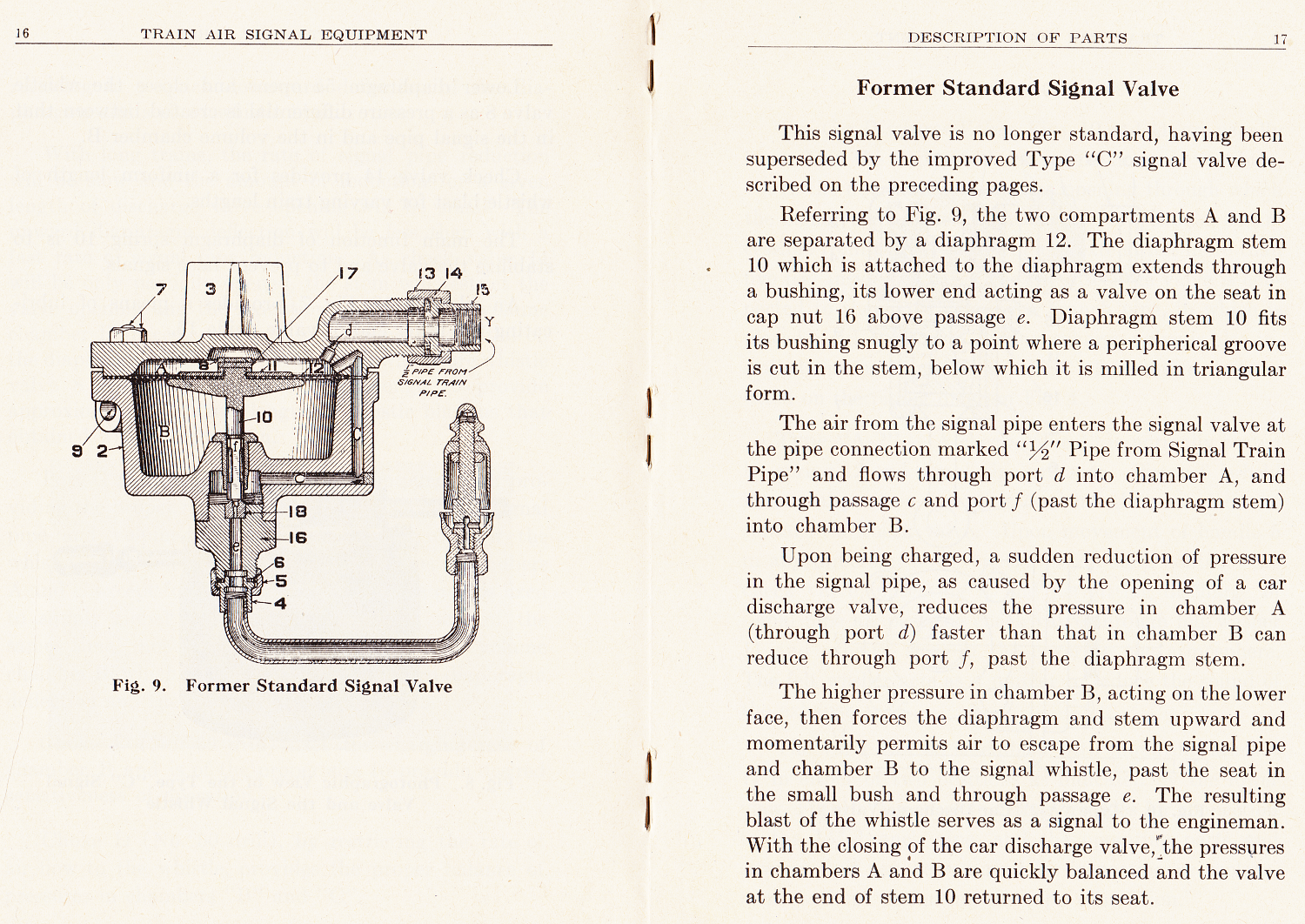

If you find the new, improved version (above) too complex, you could try the older version of the signal valve (below). It is a little less complicated and the whistle is attached!

PLEASE NOTE:

I have NOT included the descriptions or schematics of the valves and other bits

which step down the brake line pressure to the lower signal line pressure.

So parts and pages are missing here.

* * *

Things become more fun and easy with the two models of conductor's Car Discharge Valves which are shown below. Essentially, a valve is seated by a spring and it holds back signal line pressure ...

If the conductor toggles the valve in any direction by pulling on the cable threaded through the Discharge Valve's Handle eye (5) ... the valve comes off its seat ... air rushes through it - and a muffling felt washer - to atmosphere ... and a signal propagates its way along the air signal line to the Signal Valve in the cab.

The Westinghouse plant in Wilmerding, Pennsylvania is shown below in 1897.

|

| from: Wikipedia article on Wilmerding, Pennsylvania. |

* * *

From the Canadian railway rulebook (UCOR), Revision of 1962.

|

| from: Uniform Code of Operating Rules; Rev. 1962; Board of Transport Commissioners for Canada. |

While the 1962 rules were often patched and updated by railways' special instructions,

until they were replaced in 1990 by the CROR,

you'll notice that it was 1) signal line ... 2) hand signals or 3) radio.

* * *

Who knows how many gravestones were used to build Rule 16 (m) and Rule 90?

On a passenger train, the conductor was to give communicating signal (m) above ... between 1 and 3 miles before the passenger train was ... to meet a train, to clear a train, or to move through a siding or crossover. In response, the engineer was to make a running test of the brakes, then reply with whistle signal 14 (n) [two long, one short whistle sounds]. If there was no response, "action must be taken to stop the train before the point of restriction" ... If time was getting short, the conductor would probably dump the train's air.

Rule 90 in this form first appeared in the 1924 Standard Code.

* * *

|

| from: CNR Operating Manual for Locomotive Engineers; September 1966. |

48 Safety Control Whistle

50 Cab Signal Whistle

51 Overspeed Whistle

It seems likely that these little whistles were of a common design. When stopped and at the end of a freight train run in 1977 ... the engineer would take his foot/lunchpail/toolbox/travelling library off the deadman's pedal (e.g. 47 above) and I would hear a quickly-weakening warning whistle sounding very much like the communicating signal whistles.

* * *

Above, in May 1981 ... after switching at Brockville, Ontario ... a VIA passenger train has been recoupled. With the steam, brake and communicating lines recoupled (behind the VIA attendant's right knee), the next order of business is to use the communicating line (to the rear of the new joint) to request a brake test (four short sounds). The shiny silver metal of the piston rod will be seen to travel outside of the brake cylinder to the right, and the brake shoe will apply to the tread of the wheel.

In the detail to the right, you can see the conductor's fingers are extended as he waits for the previous short sound to propagate distinctly. Unfortunately, the discharge valve hardware cannot be seen clearly. Notice that the valve cable is positioned high enough that it won't be accidently grabbed or snagged by a passenger or other occupant of the vestibule.

Glowing steel brake shoes always produced a nice smoke and spark show if an engineer was coming in fast with a heavy brake application.