Sixty-two workers died in Rogers Pass.

On March 1, at Wellington, Washington on the Great Northern, 96 people had been killed by an avalanche.

Note: This post contains a historical newspaper description ... of retrieving fatalities from an avalanche ... and of railway workers based on their ethnicity.

* * *

I've never been interested in this particular disaster. However, because of 'unwanted results' I got during Google news archive searches, I became interested in it.

Having found the story below in an archive.org journal, I set off to try to find the story behind the ruling ... which was precipitated by not having appropriate tell tale warnings at Snow Shed 18. The Rogers Pass avalanche disaster happened to occur at Snow Shed 17.

|

| from: Railway & Marine World, Sep 1910 |

I never did find an account of the accident mentioned above.

* * *

To confirm that it was a different time in history which we are happy not to be living in ... consider this headline. This story was contiguous with the Ottawa Evening Citizen Page 12 continuation of the front page avalanche update - the last clipping of this post.

It is difficult to imagine people rule-of-thumbing a rabies diagnosis with their pets today. The first experimental rabies vaccine injection in a human was performed by Pasteur in 1885.

* * *

Beginning to look at the Rogers Pass 1910 avalanche, here is an overview of the area.

|

| from: Annotated Time Table; c 1905; Canadian Pacific Railway. |

|

| from: Annotated Time Table; c 1905; Canadian Pacific Railway. |

Knowing nothing, I was contemplating making a wisecrack, rhetorically asking who in their right mind would build a railway near 'Avalanche Mountain'.

I had concluded Avalanche Mountain was first named after a Canadian politician ... then it was re-named so the politician wouldn't be linked to the disaster ... and to commemorate the event.

To my surprise ... Avalanche Mountain was named by Major AB Rogers ... because ... it was a zone where numerous avalanches had been documented. The 1905 map above pre-dates the disaster.

* * *

|

| from: West of the Great Divide; Robert D Turner; 1987; Sono Nis Press. |

Above, you can see a sliver of an excellent map of CPR operations near Rogers Pass. Notice, that there was generally a winter track within a snow shed and a summer track outside it. Hot coal cinders were probably a summer fire hazard the early CPR didn't need jetted into the ceilings of its snow sheds by locomotives. As well, the wooden passenger equipment of the day would have been naturally ventilated with windows and clerestories; the CPR would have avoided displeasing passengers by fumigating their coaches with coal smoke every mile or so by using an outdoor summer track.

According to an opinion expressed in the Evening Citizen story ...

"After 20 years' experience, no slides having occurred there, the company abandoned the old line which has a grade, in favour of the new line in the open. If the old line had been still in use, the disaster would not have had such fatal results or at all events, the snow sheds would have stood a chance of resisting the awful impact."

The new line in the open was at ... Avalanche Mountain.

|

| from: Van Horne's Road; Omer Lavallee; 1974; Railfare. |

Above, is Snow Shed 17 as it appeared circa 1886. While the Last Spike was driven in late 1885, a great deal of work was necessary to prepare the new line for commercial traffic in 1886. I believe this view is looking timetable west.

* * *

|

| from: Google Earth |

Above, looking north, you can see Rogers Pass as it appears today.

The gradients depicted are probably lessened by the view I have selected.

See the image below.

* * *

|

| from: Souvenir of My Trip through the Canadian Rockies on the CPR; undated; Canadian Pacific Railway. |

Above, is a large-format photo from a CPR souvenir book.

We have advanced and turned the corner on the Google image and are facing east.

Similar to Snow Shed 17, the shed above is a 'valley shed'.

When the line hugged a mountain rock wall, the sheds were built with more of a 'lean-to' architecture.

Indeed: Mount Macdonald was named after the Prime Minister and not some hamburger clown.

* * *

The workers had been clearing an avalanche which occurred at around 1200hr, Friday, 4 March 1910.

The major loss of life occurred at around 2359hr Friday, 4 March 1910.

It is difficult to see an approaching avalanche in the dark.

It is difficult to hear an avalanche on a stormy night with a rotary snowplow working.

Intuitively, we expect that the Company ordered the line to be cleared on an urgent basis after the 1200hr blockage.

On March 12, a coroner's jury was split:

Three jurors felt the CPR was negligent, the other three decided that the loss of life was unavoidable, but that the railway should take further precautions in the future.

In West of the Great Divide, Robert D Turner states that a second coroner's journey found agreement on two points: The disaster was an accident, and the railway should avoid ordering workers to clear snow slides during stormy nights.

* * *

Here are two American articles from the US northwest.

From: The Spokane Evening Chronicle, 9 March 1910.

Above: Contemporary rotary snowplow technology.

(Tender not included.)

A rotary snowplow was not self-propelled. Its onboard steam engine had a regular steam throttle which provided variable steam power to the throwing wheel ... so the power could match the snow load being thrown.

For motive power (forward and reverse at the snow face), a regular locomotive was coupled behind the snow plow tender. It was governed by signals given by an experienced snowplow foreman. This maintenance of way management employee looked forward from the snowplow cab. The cab can be seen immediately behind the throwing wheel.

* * *

From: The Kettle River Journal, Orient, Washington, 12 March 1910.

* * *

On Being a 'Real Canadian' - 1867 to 1910

Concisely: A 'Canadian' is a British subject who has the right to remain in Canada.

Details:

Foreigners who were not British subjects could become naturalized as British subjects/'Canadians' after living in Canada for three years, fulfilling a 'good character' requirement and by taking the necessary oath. However ...

There are numerous examples in history which demonstrate that the real challenge was getting into Canada ... in order to live here for three years. For example, you might be deemed to be 'unsuited to the climate' ... or direct ship transportation to Canada might not be available from your native country (see the SS Komagata Maru incident). Maybe you were a dark-skinned American ... who seemed 'likely' to have tuberculosis, etc.

British subjects from outside Canada became 'Canadians' after the 3-year residency period.

People born in Canada (who had not subsequently denaturalized) were 'Canadians'.

In the period 1900-1910, an alliance existed between Britain and Japan which prevented outright bans on Japanese immigration or devices such as the notorious 'Chinese head tax'. Generally, Japanese immigrants could be admitted if they had government-approved work contracts ... or were domestic workers in Japanese households ... or agricultural workers on Japanese-owned farms.

A 'Canadian citizen' was first defined in the Immigration Act of 1910. As far as I can tell, the Act was the first domestic Canadian law which codified the conditions above. That is, Canadians were defined as legitimate residents of Canada and British subjects.

* * *

With all of that in mind, here are two Canadian articles.

Being big-city newspapers, the stories must reflect the prevailing social attitudes toward non-anglophone newcomers to Canada.

From: The Evening Record, Windsor, Ontario, 7 March 1910.

Unfortunately, the microfilm quality was uneven ...

* * *

I believe the following three photos were taken or published by Byron Harmon showing the March 4 disaster aftermath.

|

| The Great Glacier and Its House; William Lowell Putnam; 1982; American Alpine Club. |

The photo above is not explicitly described as having been taken after the March 4 avalanches, however it was probably taken during this event. This is the right page of a large 2-page spread. It shows the technique used to feed a rotary when the depth of snow was too great to be handled by the rotary alone.

Snow may have been shovelled uphill in relays first ... to make it possible for the rotary to clear out the bottom 10-foot layer of the 'cut' into the snowbank/avalanche (a 10-foot vertical snow face being the rotary's maximum practical capacity).

Once the rotary could operate along the rails, the labourers would then shovel the snow down the steep bank, into the trench which the rotary had created along the rails. Next, the rotary would advance and throw this snow clear of the right-of-way ... where it could safely sit until it melted in the spring.

* * *

|

from: West of the Great Divide; Robert D Turner; 1987; Sono Nis Press.

|

This photo was taken by Harmon at the March 4 avalanche site. You can see the tiers of manual shovelling which had been organized on the right side. As thick pieces of wood would damage the rotary, much of the debris had to be manually dug out and moved by hand.

As is often seen in pictures like this ... Even with the rotary spinning its throwing wheel at full throttle, as it is here, workers feel safe standing on the right-of-way in front of the approaching machine. The rotary's forward speed is very low.

* * *

|

| The Great Glacier and Its House; William Lowell Putnam; 1982; American Alpine Club. |

This undated photo shows the resumption of traffic through Rogers Pass after the March 4 events.

* * *

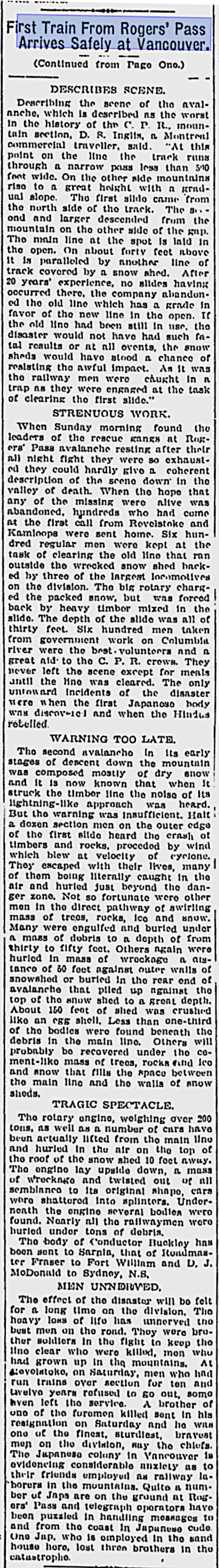

From: The Evening Citizen (Ottawa), 9 March 1910.

Apparently, these were the contemporary terms for ethnicity used in the capital of Canada.