Jim Christie found these excellent Angus Shops photos and articles from about 120 years ago. They show the building of rolling stock as well as the training of apprentices and other staff. The articles are originally from The Montreal Standard and Jim found them at Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BANQ).

Here is the first article - from 1906.

I was not able to obtain the road number from the engine at the left-centre.

* * *

Here is the second piece from The Montreal Standard from 1909.

After the newspaper laid out the photos on the pages,

they poured little bits of text into every available small space,

making it difficult to re-assemble the article as an image.

... So, the text of the entire long article appears at the bottom of this page.

In modern terms, it is like 'native text' or an 'advertorial'

for the benefit of the CPR's corporate image.

* * *

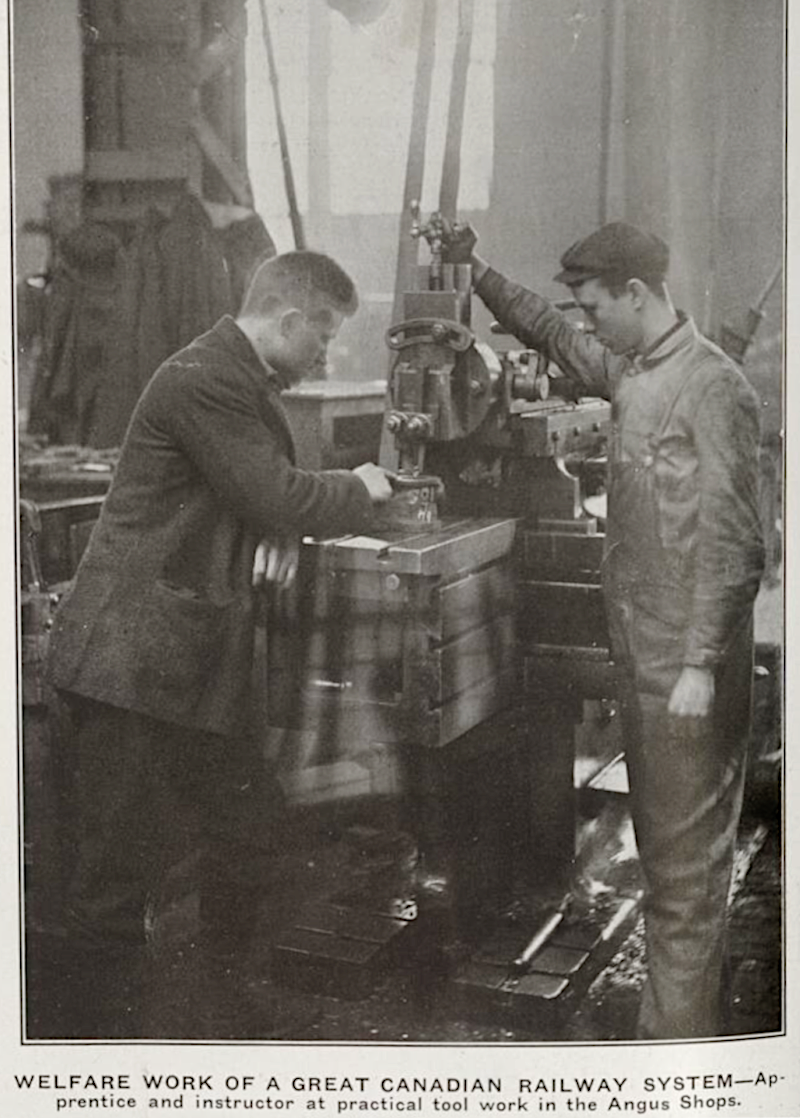

As you'll see, this article features even more interior photos of Angus, particularly in areas where apprentice and staff training took place. The facilities are typically spartan and often lit primarily with natural light. Many industrial facilities of the era were designed to make the most of free natural light through south-facing skylights and large areas of window on southern exposures.

The theme of this extended piece is the 'welfare work' of the railway for its employees. In modern terms, 'welfare work' is simply the set of progressive measures used to develop and support its apprentices and staff. And when you train your own staff you know they can be expected to follow your own procedures. They will not bring in bad habits learned on another railway or in another shop.

... When you are training young people, you develop a better understanding of who should be hired permanently in a given field, and who might be better suited for employment in another department. Perhaps some should not be hired at all.

During this era ...

... In railway operations, it was often a 'military model' which was imagined - with the dispatcher as the field general issuing terse, telegraphic orders via, and to, his subordinates. Otherwise the foot soldiers were to rigidly abide by the rulebook and the timetable.

... In manufacturing, it was often Taylorism - the 'scientific approach' developed through time and motion studies. The ideal was to minimize wasted time and maximize employee productivity. After an efficient system was designed, employees became interchangeable pieces of the assembly line.

... Angus is often referred to with a nostalgic, wistful sigh by historians steeped in CPR mythical lore as being legendary - probably because of the distinctive-looking motive power it developed and/or built. On the other side, in reality, it was an enormous, dirty, too hot/too cold, noisy, often dangerous, heavy-industry factory, near the headquarters of a penny-pinching corporation. That was just the nature of large railway shops. The boss didn't arrange for birthday cake and 20 minutes off in the break room to celebrate that month's employee birthdays. Employee's didn't buy World's Best Boss mugs for their supervisors.

... In the non-corporate-lore Angus Shops histories: Communication between the workers and the administration at Angus was expected to be in English. Higher level staff with railway expertise and experience were often imported from Britain and the US - so professionals and other experts were even less likely to know a second language than native Montrealers who spoke English. But, to be effective, supervisory personnel would have to be fluent in both English and Quebec French to get the best from their workers. These supervisors would usually rise up through the ranks from 'entry level positions'.

These elements probably describe the 'human experience' of CPR employment in the 1900-1910 period at Angus.

If students could concentrate on accurately sending and receiving in this setting,

they could probably work anywhere!

Some students seem to be sending, while others are recording the messages.

At the back, perhaps that is a three-element gas light which has been retrofitted for electricity.

The wood-gluing presses (leg fracture photo)

and the passenger car wall panels and components (fractured skull photo)

... are the unique features of these two first-aid photos.

I think the labour behind this kind of effort was largely done by the live-in agent and his family.

Awards were given for the most attractive gardens and parks.

Obviously, the Company's 'welfare' was also helped if customers found its property attractive.

The railway-YMCA combination was fairly common - at least on the CPR in northern Ontario. The engine crews and other employees from out of town (for example, temporary low-seniority operators, bumped spareboard firemen, etc) could find a room here. Of course, the train crews (conductor, trainmen) slept in the conductor's assigned van (caboose) until ordered back to their home terminals.

In Chapleau (if it was like White River) the CPR stationary steam engine which provided electricity for the railway facilities might have also supplied steam heat for the for nearby company buildings like the railway YMCA.

The photographer visited the railway YMCA hearth below during warmer weather, so no fire is burning. A nice verandah was sometimes built into the peak of the roof and it was probably enjoyed during the summer.

* * *

One last image from the 1906 article at Angus ...

If my 'math' is correct, the 1106 was built in 1906, in the G1C class,

with the Angus serial number 1486.

After a few decades, rebuilds and renumberings, it was scrapped in May 1961 as the 2206.

Perhaps that is an acetylene headlight with its components exposed.

* * *

The newspaper article from 1909 ...

Welfare Work of a Great Canadian Railway: The Systematic Improvement of Young Employees

In all the great military schools of to-day is taught the importance of proper food, sanitary conditions, suitable clothing and modern weapons for the army. The captains of industry in this great land of ours have not been slow to find out that it pays to treat their army of workers fairly, and to give to them the very best tools, the most favorable conditions for the performance of their duties, is an investment productive of good returns. In the keen competition in the industrial world of to-day the victories of peace and profit must come by obtaining the best results from the laborer and mechanic. At the head of the vast army of railroad employees, and controlling for the shareholders the immense property of the Canadian Pacific Railway are alert, shrewd brains at work planning and directing; also there are hearts that recognize in the humble worker in the ranks a man like themselves, and for the general good of the service is required his hearty co-operation to obtain the greatest success for the company. Which means the comfort and safety of the travelling public, dividends for the stockholders, and more business for the road.

Welfare work may be said to consist in the efforts of the management on behalf of the employe over and above the payment of wages. Making him more comfortable and contented in his work, and robbing old age of its terrors by means of a pension fund. Now, this railroad does not say that their motive in this work is purely philanthropic. They frankly confess that considerate treatment toward their employes is for them a paying business.

The new improvements in equipment, the enormous increase in traffic, has made railroading much more exacting in its requirements from the men who engage in it. This business, possibly more than any other, requires the clearest heads, the steadiest nerves and the strongest muscles, for the reputation of the road must always be safe-guarded. Therefore, the type of men operating their trains, building their cars and manning their ships is of the greatest interest and importance to the company. It is most important to this company how their men spend their spare hours, when off duty, even though they exercise no jurisdiction over them; thus they are willing to help to provide healthful, pleasant, wholesome recreation, and opportunities for mental and physical improvement. Considering the great numbers of skilled workers required for the work on the railroads, it is not at all surprising the company should take a very active interest in training their men for the service. The recognized policy of this progressive road is to give to their young men every encouragement to learn their business thoroughly, and to qualify for advancement to higher positions.

Each year a larger amount of money is being devoted by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company to this special work for their employes. That the efforts and expense in these various departments on behalf of workers have been abundantly justified from both the business and the humanitarian standpoints, the higher officials of this road are firmly convinced. It has brought the men and the management into closer relationship. It has made the employees feel that the company takes a sympathetic interest in their welfare; that it is not merely trying to grind out the best years of their lives with exacting work, long hours and small pay without giving them anything to look forward to but retirement without compensation through disability or old age. This welfare or betterment work has done much to stamp out that spirit of discontent that used to be so prevalent among railroad workers. It has generally raised the tone and character of the men, increasing their loyalty and efficiency, and helping them to realize that the success of the company that employs them means their own success, and that these both depend upon each worker doing well his own part.

Here are some examples of the nature of this work:

Work for Apprentices.

The company has inaugurated at their Angus Works, Montreal, a new system for handling their apprentices. This new system, based on broad, common-sense lines, has become well established, and while much remains to be accomplished, the splendid progress made thus far and the strong organization which is being built up, promises well for the future. The management. is not looking for immediate results; for they are farsighted enough to think five, even ten, years ahead; sure that their present efforts will be rewarded when that time elapses.

The young recruit, when seeking admission, has to satisfy the management as to his general intelligence and good health. When in the workshops, the future mechanic is put through a systematic and continuous training, which, upon completion of his apprenticeship, enables him to qualify for a mechanic’s position, and then, by further instruction, advance to the highest positions in the organization. Every facility is placed in the way of the ambitious and intelligent employee to receive instruction from qualified and experienced officials in shop and railroad work. The trend of this preliminary training has the tendency to create a desire in the aspiring employee. The training is progressive; starting first with educational instruction for the young employees, then advancing to shop and educational instruction for the apprentices, and finally the journeyman receives educational facilities which enable him to qualify for minor positions on the staff.

The moral and physical side, as well as the mental, is covered by the training given, and it is interesting to see what this railroad is doing towards the development of its employees.

Primary Education for Young Employees.

1. Reading and writing.2. Elementary arithmetic.3. Geography of the C.P.R. System.4. Biographical sketches of past and present eminent Canadians.5. Freehand drawing.6. Punctuality and regularity.7. Thoroughness, application and self-reliance.8. Cleanliness and thrift.9. Recreation.

The young employee, after he has received the above training, is put through courses of instruction in shop arithmetic, shop mechanics, shop practice and mechanical drawing, which enables him, upon completion of his apprenticeship, to qualify as a skilled mechanic. Then, if necessary, he may take advantage of the advanced classes in mechanical, electrical, boiler and car work, etc.

A very interesting feature of the training is the practical work of the boys in the work shops, which is carried on under the direction of skilled shop men who are termed shop instructors. These men are carefully selected, as they are held responsible for the moral as well as the practical training of the boys. The educational side of the training is carried on in a room set apart for the purpose, and well equipped with desks, tables, blackboards, cupboards, etc. The apprentices attend the instruction classes during working hours, and for the time thus spent the boys are paid their regular wages. The instruction classes are under the charge of practical and technical trained men who are termed educational instructors. The chief Educational Instructor, Mr. Henry Maxwell, is a man with a large heart, and kindly feeling for the boys.

In order to encourage the deserving apprentices, the company donates each year a scholarship to the ten best apprentices. These scholarships consist of complete courses in mechanics, electrical, boiler work, etc., issued by the International Correspondence Schools, Scranton, Pa. The company also awards two scholarships, tenable for four years at McGill University, Montreal, each year to sons of employees. The holders of these McGill University scholarships are employed by the company during vacation, and receive remuneration for their services.

end of available text