In the late 1800s, when wedge plows pushed by steam locomotives were not successful in 'bucking' through snow drifts and avalanches, it was necessary to put gangs to work to manually shovel the snow from the track. The Canadian invention of the steam-powered rotary snow plow was developed to make rail transportation more dependable ... and to make winter maintenance of way work less labour intensive.

Thank you to Jim Christie for the archive.org references he has sent me (over a period of years) about rotary snow plows - they were key in creating this series of posts.

A concise article on the early development of rotaries was written by Dr RVV Nicholls and can be found in the March 1967 edition of Canadian Rail. At that moment in history, Nicholls and the CRHA had just been successful - at the last minute - in saving the only remaining standard gauge Canadian rotary snow plow. It was about to be scrapped at London, Ontario. It is preserved in the museum at CRM/Exporail.

* * *

Around 1885, as the first Jull/Leslie-designed ... Patterson, New Jersey-built ... rotary snow plows were tested, it became obvious that several improvements were desirable. To properly prepare the track for traffic and to protect the plow from derailing, flangers (for snow) and ice cutters were mounted on the front of the leading truck. This ensured that the rail was 'clean'. A chute which could send ejected snow to either side of the track was also seen as a necessity.

An 1885-86 trial took place in northern Iowa using the original counter-rotating two-wheel system of the original design. The first wheel worked like a multi-bladed rotating kitchen grater - to shave a layer of snow from the bank to be moved. The second wheel looked and worked like the paddle of a paddle-wheeled steamboat to bat the snow out of the snow plow via the chute.

|

| Jull patent drawings ... from: Rotary Ploughs, A Canadian Invention; Dr RVV Nicholls; Canadian Rail, March 1967; Canadian Railroad Historical Association. |

The problem with the two-wheel arrangement was that too much energy was wasted as the snow moved from the grater/impeller wheel against the counter-rotating inertia of the paddle wheel.

|

| Jull Patent drawings ... from: Rotary Ploughs, A Canadian Invention; Dr RVV Nicholls; Canadian Rail, March 1967; Canadian Railroad Historical Association. |

* * *

The improvement consisted using a single wheel with all the snow-moving features attached to it - so everything was moving in the same direction. On the front were self-adjusting auto-reversing knives. On the back were radial partitions which flung the snow out of the chute.

Essentially, the new single wheel still provided a 'two-stage' process - impelling and throwing - but it used a single wheel at its core. And when its driving engine reversed the wheel ... the snow-moving features were automatically fully reversible.

This new design sold itself during the winter of 1886-87, when J.S. Leslie personally operated it, to open the 70-mile Oregon Short Line Division of the Union Pacific. Impressed, the railroad purchased the plow and several other American railroads followed with orders as well.

|

| from: Engineer's Witness; Ralph Greenhill; 1985; Coach House Press. |

In 1888, the CPR worked with the Polson Iron Works of Toronto to begin to build eight of its own rotary snow plows. One example of the CPR's first set of rotaries is seen above. Notice the use of wood to construct the body of the plow. The engine's smokestack can be seen behind the word 'snowplough'. The cab and tender are protected from the weather, and any wind-borne snow from the rotary's chute, for the benefit of the fireman and engineer operating the rotary's wheel-turning steam engine. Rotary snow plows were not self-propelled.

As seen with the previous post on the Alco rotary snow plows (and the patent drawing above), the reciprocating force of the snow plow's steam engine pistons must change direction before it turns into the rotary motion of the wheel.

... Because early rotaries used the 'conventional steam locomotive layout' of putting a piston with its own valve gear on each side of the plow's boiler ... one of the weaknesses of these plows was the gear necessary to convert and transmit this power.

The CPR determined that further refinements were required for future rotaries. When the plows nosed into hard-packed snow and ice (as created by an avalanche) a lack of rigidity in the plow's frame caused internal stresses in the transmission. Sometimes this lead to on-the-road failures of the bevel gears transmitting the power from the pistons to the wheel.

Furthermore, the wet snow of the Selkirk Mountains was harder to eject, clogging the 'throwing partitions' on the back of the wheel. The 'conical scoops' design, shown in the Alco wheel in the post above, was helpful in dealing with this problem.

|

| from: Rails in the Canadian Rockies; Adolf Hungry Wolf; 1979; Good Medicine Books. |

Another view of the first series of CPR snow plows. Undated, no location indicated.

|

| from: archive.org |

* * *

A New Design

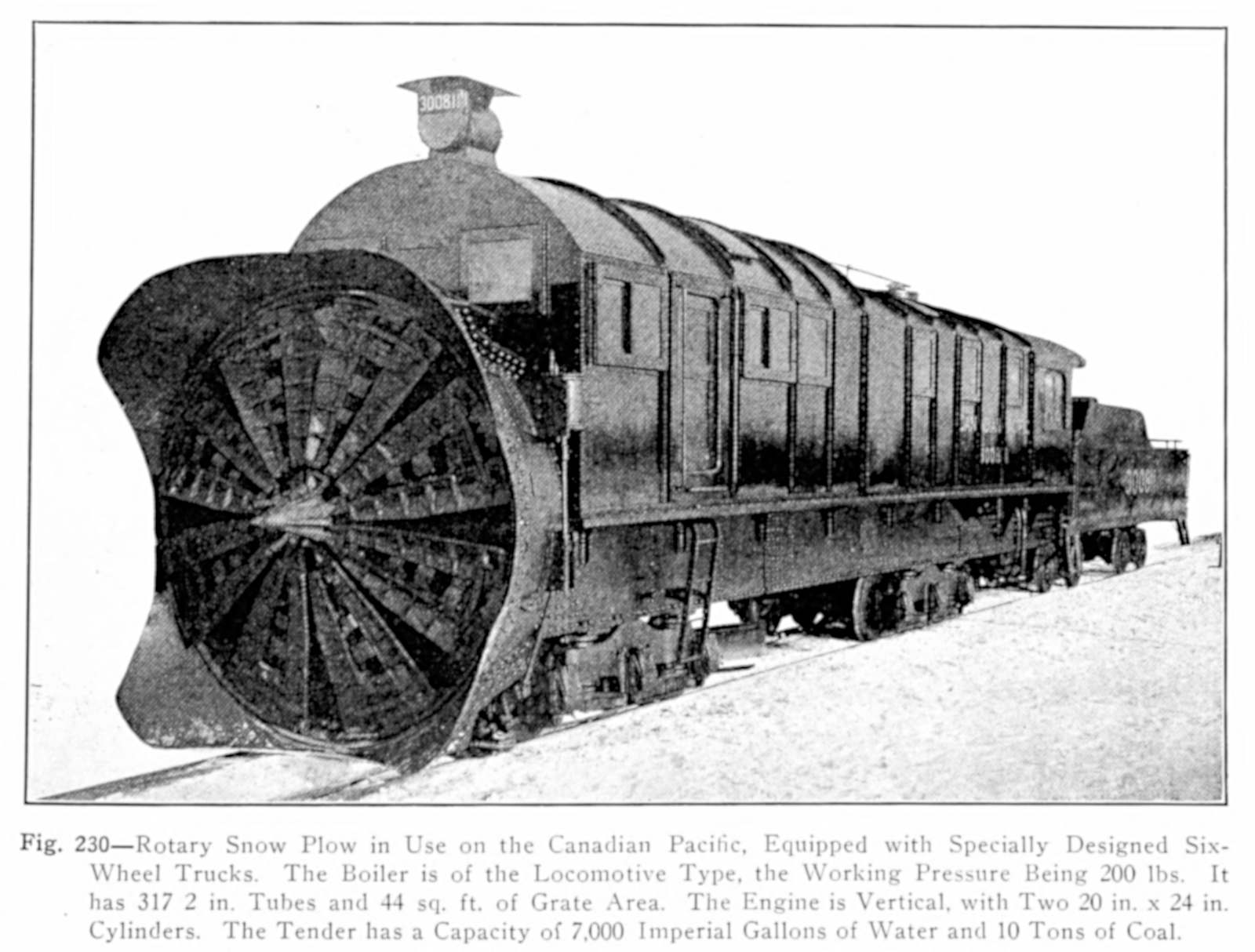

Henry Hague Vaughan, Assistant to the Vice President of the CPR for motive power from 1904 until 1915, was behind the creation of two unique CPR-designed plows for service in the western mountains. They were intended to solve the problems noted in the earlier rotaries, above.

One's first reaction might be that these plows are not as attractive as the original series - at least when those original plows were new. However, the railway was not sending the new plows into the mountain avalanches of snow, ice, rocks and trees to be admired for their aesthetics. The new plows were designed to be able to ingest trees of up to 4 inches in diameter.

Vaughan wrote much longer articles for professional journals extolling all the design features of these plows.

|

| from: Apr 1911, Railway & Marine World, Jim Christie. |

|

| from: Apr 1911, Railway & Marine World, Jim Christie. |

Notice the use of a marine engine - so the rotation of the engine's main shaft is transmitted straight to the wheel ... just as power would be transmitted straight to a ship's propeller. However, with the determination to build these 'battleships' came the need to find reasonable compromises so that their sheer weight wouldn't cause more problems on the road than it solved. Drawings of the the unique six-wheel trucks appear below.

|

| from: Apr 1911, Railway & Marine World, Jim Christie. |

|

| from: Car Builders Dictionary, Master Car Builders Assn 1913, archive.org. |

|

| from: Car Builders Dictionary, Master Car Builders Assn 1913, archive.org. |

* * *

CPR Rotary Snow Plows in Later Life ...

|

| from: Canadian Pacific in the Rockies, Vol 4; DM Bain; 1979; BRMNA. |

Above: One of the first class of rotaries awaits a call to duty at Hope BC in August 1929.

This machine was kept on the roster from 1888 until circa 1950.

|

| from: Memories of Canadian Pacific Steam Power in British Columbia; Jim Hope, Donald Bain; 1996; BRMNA. |

Above: In April 1943, one of the two Vaughan-conceived rotaries sits with a tender full of coal at Revelstoke.

After World War 2, with the wide availability of caterpillar-tracked, diesel-powered construction equipment,

the end was in sight for rotary snow plows.

* * *

Other Canadian Railways

|

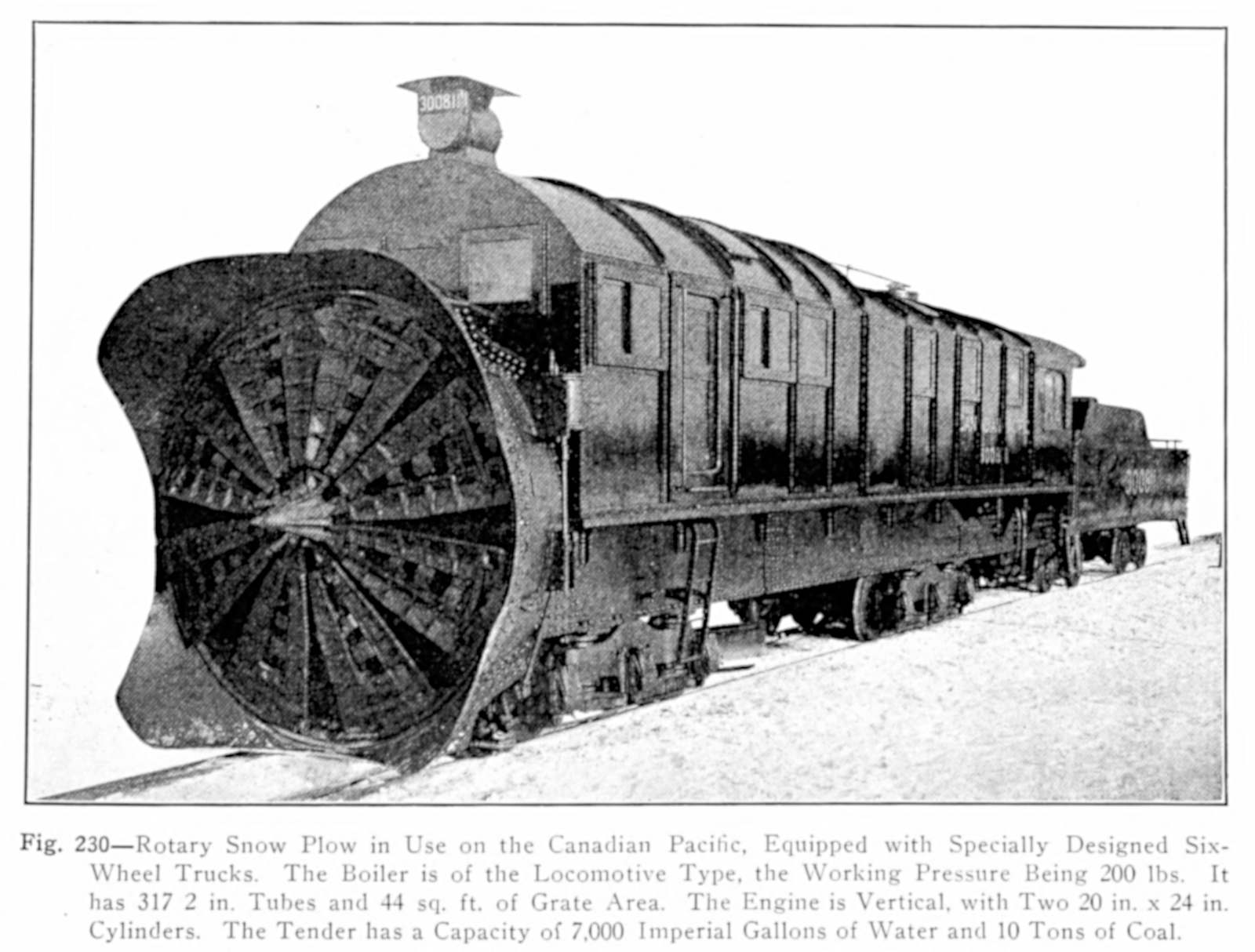

| from: Car Builders Dictionary, Master Car Builders Assn 1913, archive.org |

Early in the 1900s, there were many opportunities to use rotary snow plows in Canada.

The western mountains received plenty of Pacific Ocean precipitation ... and avalanches onto the railway rights-of-way which followed mountain river valleys. On the Prairies, blizzards whipped the region's typically dry snow into huge, hard-packed drifts - particularly in cuts and depressions. The region of Lac St Jean, Quebec was another CNR territory which often called for rotary plow operation. And on Newfoundland's famous Gaff Topsail, storms coming in from the Atlantic Ocean created depths of snow which defied railway operations and necessitated a regular rotary presence.

|

| from: The End of the Line; Clayton D Cook; 1989; Harry Cuff Publications. |

An Alco-built rotary in Newfoundland. No location given, undated photo.

* * *

|

| Stan Stiles photo, collected by LC Gagnon. |

July 1954 at Kamloops, BC.

Notice the temporary draft gear on the front of the plow.

* * *

In the United States ...

|

| from: The Central Pacific & Southern Pacific Railroads; Lucius Beebe; 1963; Howell-North Books. |

Above is an experimental rotary designed by Orange Jull, built by Rogers in Patterson NJ.

It was tested on the Central Pacific in 1890 and abandoned as a design.

* * *

|

| from: Northern Pacific, Main Street of the Northwest; Charles R Wood; 1968; Superior Publishing. |

Captioned as the Mosquito Creek Bridge in 1887, this photo shows the practice of running a consist with rotaries on both ends. Where avalanches were common, this protected against most eventualities. The distant rotary is blurred into the book's gutter, but you can see that an elongated car which has been tarped over is being used as a tender behind that rotary.

During western US railroad construction, switchbacks were sometimes used over the mountains ... until summit tunnels were completed to reduce the permanent main line's gradient. During some blizzards, a double-ended rotary consist could barely manage to keep the switchbacks open.

* * *

|

| from: The World's Work; 1905; Doubleday Page & Co. at archive.org |

David Moffat was a banker, regional railroad builder and Denver 'booster' who was behind the construction of the Denver, Northwestern and Pacific Railway. This line was intended to complete a connection between Denver, Colorado and Salt Lake City, Utah. Before the 6 mile long Moffat Tunnel was opened in 1928, the railroad followed a tortuous path via Rollins Pass. If you click the link to the circa 1905 Alco booklet at the top of this post, you'll notice that this particular rotary snow plow DNW&P 10200 is presented as a featured illustration.

CPR 1915 data for comparison: The summit of Kicking Horse Pass is 5332 feet; the summit of Rogers Pass is 4340 feet.

* * *

|

| from: Lines West; Charles R Wood; 1967; Superior Publishing. |

In this undated photo of the Marias Pass in the Montana Rockies, bulldozers have reduced the extent of a snowslide to the depth which can be handled by a Great Northern Railway rotary. Two short snowsheds of classic design can be seen in the distance.

Later in their careers, some rotaries were oil-fired. Today, a few rotaries are still in use and most have been rebuilt to be driven by diesel-electric prime movers.

* * *

Rotaries in 1914

This book is preserved at archive.org.

One can probably assume that railways operated rotaries if they had applicable contract language.